PAUL WILLIAMS

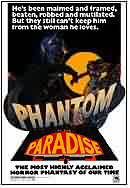

THE MAKING OF

PHANTOM OF THE PARADISE

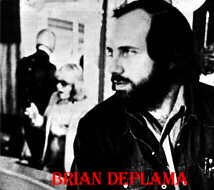

An Interview with Brian De Palma

(from Filmmakers Newsletter)

February 1975

By John Coates

John

Coates: PHANTOM is something you've been wanting to do and trying to do

for half a decade. Where specifically did the idea of doing the movie as a

send-up of PHANTOM OF THE OPERA come from?

Brian De Palma: I wrote the first treatment for

Filmways in 1969. I had the idea that rock was developing as a Grand Guignol. I

was sitting around one night with a young NYU film student and a friend of his,

talking about ideas for movies. We were all into the idea of rock music, and one

of the kids came up with the idea of the Phantom of the Fillmore. I said,

"That's terrific!" The notion of a contemporary opera house being haunted by a ripped-off composer was very appealing.

JC: Did you look closely at the original PHANTOM before you started writing?

BDP: Not really. I remembered it, of course, and had seen it a couple of times, and I think we did look at it soon after. But I mostly remembered the classic scene at the end, the phantom at the organ.

JC: Did you know the leading lady's name was Mary Philbin in the original? Or was that totally coincidence?

BDP: Yes. The character's name at first was Arnold

Philbin, and then I just called him Philbin.

JC: What about the considerable legal problems that came up?

BDP:

The book is owned by Universal Pictures, and of course they own the three film versions: one with Lon Chaney, one with Claude Rains, and the third starring Herbert

Lom. When we finished the picture, Universal told us they felt we were infringing on their story line -- not so much the book, but some of their later versions, and the 1962 one in particular (which I mostly remember for Herbert Lom and the terrible set). So we had to settle with them for the rights in order to prevent the film from being held up from distribution. If we had gone to court I'm sure we would have won, because I don't feel we were infringing on the story lines of those versions. And there are many famous cases of parodies of forms -- like the famous Sid Caesar parody of "American Tragedy."

BDP:

The book is owned by Universal Pictures, and of course they own the three film versions: one with Lon Chaney, one with Claude Rains, and the third starring Herbert

Lom. When we finished the picture, Universal told us they felt we were infringing on their story line -- not so much the book, but some of their later versions, and the 1962 one in particular (which I mostly remember for Herbert Lom and the terrible set). So we had to settle with them for the rights in order to prevent the film from being held up from distribution. If we had gone to court I'm sure we would have won, because I don't feel we were infringing on the story lines of those versions. And there are many famous cases of parodies of forms -- like the famous Sid Caesar parody of "American Tragedy."

JC: I would have thought that since PHANTOM is basically a lampoon, although sometimes a serious one, the case wouldn't have held up. Why not go to court with it?

BDP: Time. We were in the midst of very delicate negotiations with the distributor. In order not to blow that deal, or rather, make them hold up distribution until February or March, we felt we should settle this as quickly as possible so we could get the film out in October. There are other films which are somewhat in the same genre -- although this isn't a real genre yet -- and I wanted to get out first.

JC: But you made this completely independent of any knowledge of those?

BDP: Absolutely. But it's like seeing a sociological development that a lot of other people see too. Although they're all working quite separately, they're all influenced by it.

JC: By sociological development you mean the Grand Guignol aspects of rock you mentioned before?

BDP: Right. The performing rock people themselves are going into the weird and the fantastic -- which, of course, is an area very close to film.

JC: Did you use anyone in particular as a model for Beef's outrageousness?

BDP:

Well, generally, the glitter rock world. You have to laugh at it, it seems to me; I mean, you can't really identify with that world: all these pubescent kids arriving in glitter, jeans, and heels a foot high, those unisex outfits. It's so bizarre I find it hard to understand just where it comes from. Maybe it's just a matter of putting on makeup at a certain age -- I don't know.

BDP:

Well, generally, the glitter rock world. You have to laugh at it, it seems to me; I mean, you can't really identify with that world: all these pubescent kids arriving in glitter, jeans, and heels a foot high, those unisex outfits. It's so bizarre I find it hard to understand just where it comes from. Maybe it's just a matter of putting on makeup at a certain age -- I don't know.

JC: To go back a little, you first wrote this in 1969 for Marty

Ransohoff. What became of it then?

BDP: Well, because it didn't look like Marty was going to get it done, I bought it back again and sold it to Ed Pressman, and he ultimately produced it after SISTERS.

JC: After Pressman got it, how long did it take before you actually started shooting?

BDP: About two years.

JC: Was that because of the difficulty of finding backing, or the difficulty of mounting a project like this within a restricted budget?

BDP: Both. First of all, if it's a very unusual project, it's hard to convince a studio that it's something that's going to be big, a ground-breaking movie. And studio people are so far away from the rock scene.

JC: Did you find that studio people knew anything at all about the rock scene?

BDP: No. They didn't even know about things as big as Alice Cooper.

JC: So this was totally alien to them?

BDP: There's a real generation gap.

JC: They must have really thought this was weird.

BDP: Well, the idea, Phantom of the Fillmore, sort of made sense to them; they liked that. But they thought it was just a fantastic idea rather than something that was happening in theaters all over America because, of course, they never went to concerts like that. And if they didn't see WOODSTOCK or one of those films, they couldn't know about it. They're just not a music-oriented group.

JC: How did you present the film to them? As a musical primarily?

BDP: Yes. As a horror-rock musical. Film people have had notoriously bad luck at making inroads into the rock market. The only way they have really done it involved filming rock concerts that had already taken place -- you know, just have good enough stereo and draw your rock audience. I don't know if the people who go to see LADIES AND GENTLEMEN: THE ROLLING STONES are necessarily a film audience; I would think instead they're people who couldn't get in to see the Rolling Stones. So the movies they're making play right to the rock audience, but they don't have anything to do with the movie audience.

JC: And yours will, hopefully, draw as much, if not more, of a movie audience?

BDP: Because basically it's a movie. But unlike a movie musical where people just burst into song, all the music is done in performance. That's the way CABARET was done. But in CABARET they should have let the music be a kind of metaphor for the story -- if it's about money, have a number about money, if it's about love, a number about love. That's a kind of Brechtian thing where the musical numbers become a kind of ironic commentary on the dramatic action.

But

in PHANTOM all the singing is in performance: people sing when they would sing in a live performance or in an audition or something like that. That's why I think the movie never stops. The musical numbers don't hold back the dramatic action. Traditionally, musical numbers have always held back dramatic action: everybody sat down while they sang a song. But PHANTOM doesn't have that problem. Somehow the music doesn't stop the story; there are always things happening dramatically which are simultaneously relative to the musical number.

But

in PHANTOM all the singing is in performance: people sing when they would sing in a live performance or in an audition or something like that. That's why I think the movie never stops. The musical numbers don't hold back the dramatic action. Traditionally, musical numbers have always held back dramatic action: everybody sat down while they sang a song. But PHANTOM doesn't have that problem. Somehow the music doesn't stop the story; there are always things happening dramatically which are simultaneously relative to the musical number.

JC: How did you shoot the musical numbers? Was all the music pre-recorded and done to playback on the set?

BDP: Yes, all the music was pre-recorded by the group that sang in the movie. The only performer who does not do his own singing is Beef, who was dubbed in by a singer called Ray Kennedy.

JC: So when it came time to do the actual numbers, they were doing lip sync?

BDP: Yes. They would have a cassette and go home and play the tape over and over again so they could do it. We had very little problem with that. The sync holds very well for almost all the numbers, and I tried to conceive of a way of visualizing each number that would be different. For instance, the Phantom's first number is a 360 degree pan because essentially it's a simple number; it's just him at the piano in an empty club. So that was the best way to do that.

In the more elaborate Frankenstein number I had all kinds of ideas, like having the group actually chop up the audience. But I really didn't have the time to shoot them all because I was using a live audience and the ideas involved too many set-ups, so I had to simplify. But I tried to give each number some kind of filmic sense, rather than having it just look like "Midnight Special."

JC: How long did the movie take to shoot?

BDP: Close to ten weeks.

JC: Was that the original schedule?

BDP: About seven. And of course, we were shooting at Thanksgiving and Christmas, so we lost days. We also moved locations. We shot all the sets in L.A. and then moved to Dallas to shoot the interior of the Rock Palace and then to New York for the exteriors of the city.

JC: When was all the split-screen done? During the primary shooting, or subsequent to the shooting?

JC: When was all the split-screen done? During the primary shooting, or subsequent to the shooting?

BDP: No, during the primary shooting. It took me a day to stage the Beach Boys' number, and it took me another day to shoot it. We had two blimped cameras on heavy dollies. First I wanted to shoot it in 16mm so it could be handheld because I didn't think the cameramen could move in and out of each other without being seen. But the cameramen didn't want to do that. Larry Pizer, the director of photography, was worried about the quality. They didn't want that cinema verite look, so they talked me into having heavy blimped Panavision cameras. That made it like choreographing two tanks.

You've got two separate camera crews trying to avoid seeing each other, so the shot didn't turn out as complicated as I wanted it to be. With 16mm I could have gone in for tighter close-ups, for instance. So you've got a big shape on one side of the screen. I think the images are too loose for the most part, but that was the only way to go with that kind of equipment. If I had had more time and different equipment, I would have done it differently.

Also, there's a great difference in the operation of the two cameras. We had a great English operator, Ron Taylor, but we had to use a secondary operator on the second camera. And, of course, any kind of operation mistakes are doubled when you have two set-ups going simultaneously. If one guy makes a mistake, you have to start all over again, no matter how well the other camera is doing. The second operator just wasn't as sharp as Ron was. We had to go back many times because he just couldn't anticipate the other camera coming, action crossing, things like that. I think there were about 23 takes on that shot before we got it -- per camera, using two cameras simultaneously.

JC: Your work can be characterized in one way by the fact that you're the only director who consistently uses split-screen. Do you have an aesthetic reason for that, or is it just a matter of practicality?

BDP: No, I think split-screen is just an element of film grammar, like close-ups, or pans, or tracking shots.

JC: Then why isn't it used as commonly as any of those?

BDP: Because it's complicated. It takes expertise and a certain amount of experience. I shot a whole film in split-screen, DIONYSUS IN '69, which made me see, just in the crudest sense, how split-screen could be used to compress action or play one action off against another action. But I don't think many directors have had that kind of opportunity. Most people, when they use split-screen sequences, turn it over to an optical house or get someone like Pablo Ferro to come in and conceive some kind of gimmicky graphics. But they don't THINK in split-screen. I'm not trying to be tricky -- it's more like using the right word at the right time.

JC: Did you originally conceive the Beach Boys scene as a split-screen sequence?

BDP: Absolutely. I thought it was a great way to shoot a number. Also, you're generating a lot of tension on the other side of the screen with that time bomb. And on the time bomb it's good to hold one continuous shot because we know the bomb is going to go off in four minutes. So you can look at your watch -- tick, tick, tick -- and know there's no intercutting; there's no playing with the time values at all. And meanwhile you can run the musical number on the other side of the screen.

JC: Were the special effects expensive?

BDP: Not really. For instance, for Beef being electrocuted, we had a neon lightning bolt on a wire and when it hit we had charges go off. We blew up the Beach Boys' car onstage -- and it was an incredible explosion because nobody thought it was going to be that big. We had the car rigged and four cannons going, but everybody thought it was just going to be a little puff and the hood would go off. Instead, it was this immense sort of holocaust that lit up the whole stage. It was kind of scary.

BDP: Not really. For instance, for Beef being electrocuted, we had a neon lightning bolt on a wire and when it hit we had charges go off. We blew up the Beach Boys' car onstage -- and it was an incredible explosion because nobody thought it was going to be that big. We had the car rigged and four cannons going, but everybody thought it was just going to be a little puff and the hood would go off. Instead, it was this immense sort of holocaust that lit up the whole stage. It was kind of scary.

JC: Was it a real explosion?

BDP: No! We had a special effects man who gives you the largest explosion he can safely do -- that's what his job is. And then when Philbin gets hit with the bullet, again, we used a rather large charge so it looked really effective.

JC: Was it your original conception to have Swan played by the person who wrote the music for the film, as Paul Williams in fact did?

BDP: No. My original conception was to get a super-group like The Who or the Rolling Stones to write the whole score. But, of course, you couldn't even get them on the telephone. What is good about Paul Williams is that he's sophisticated enough as a composer to be able to write satiric music of a certain form. I mean, he can write Alice Cooper-type music and he can write 50's Beach Boys-type stuff.

BDP: No. My original conception was to get a super-group like The Who or the Rolling Stones to write the whole score. But, of course, you couldn't even get them on the telephone. What is good about Paul Williams is that he's sophisticated enough as a composer to be able to write satiric music of a certain form. I mean, he can write Alice Cooper-type music and he can write 50's Beach Boys-type stuff.

But what he does is make fun of that kind of music. He doesn't imitate it; he's trying to make it understandable to an audience that wouldn't necessarily understand Alice Cooper or why people are interested in him. So it's more of a movie form -- like the way "Bye Bye Birdie" makes show songs out of 50's rock. I think that works quite effectively because it makes rock understandable to people who are not rock concert-goers, which is the audience this movie is geared toward.

We tried to play the Phantom's classical aesthetic against the pop music, always keeping in mind that the Phantom had to be quite serious. I felt that when you laughed at the Phantom -- when you identified with the other characters ripping off the Phantom -- you had to laugh at the Phantom's expense, which ultimately became more and more painful as the movie went on.

JC: Are you saying you think the fact that the music is more mainstream works for the picture?

BDP: Yes.

JC: Let's make a distinction: does it work better for audiences or for the movie? Do you think the movie would have been better qualitatively with more music that was more deranged and esoteric?

BDP: That's hard to say because I like the music quite a lot. Now, I'm not a great rock buff, but I can understand the songs that are in the movie. And I like to listen to them a great deal. Again, we weren't making a movie for sophisticated rock people. That's why I think we'll get a lot of backlash from music people who'll say, "This isn't Alice Cooper or Mick Jagger."

JC: Or they may put the music down for not being rock.

BDP: Which it isn't. But I think the most successful scores that have worked in the commercial sense are things people would laugh at, like HAIR -- I mean, can you really take that seriously as a rock score?

JC: Can you tell me how you first got the idea to use Paul Williams?

BDP: Well, I had such a hard time selling the script to a regular movie company that I thought I'd come at it from the other way around: get a record company interested in it and then a movie company. I went to A&M Records and there was a young executive there named Michael Arciaga who handled their movie projects -- like putting movie scores on records. He liked the project quite a lot. He happened to be a very good friend of Paul Williams, who is an A&M artist. One day I saw Paul Williams walking out of the room, and suddenly the image of this bizarre rock impresario -- this Napoleon of rock -- came to mind. I knew too, of course, that Paul was an actor; he used to act before he became a song writer.

On the other hand, I had always thought of Bill Finley as the Phantom. I wrote the part for him, in fact. He's been in a lot of my movies, even the student stuff.

On the other hand, I had always thought of Bill Finley as the Phantom. I wrote the part for him, in fact. He's been in a lot of my movies, even the student stuff.

The girl presented a problem not only because she had to carry the part but because you had to think she was wonderful and want to love and protect her the way the Phantom did. We looked at a whole bunch of girls and finally tested about six, and Jessica Harper's screen tests held one's attention more that anyone else's. She had a kind of haunting image on the screen that I really liked. I didn't want a gutsy Janis Joplin who'd burn up the screen. And also, in horror movies, all the girls are sort of passive girls on pedestals. They are only the girls the monster falls in love with; they don't really have too much character. So I deliberately kept her pretty and sweet. Of course she also sang well.

JC: You're really fond of genre forms.

BDP: That's because I like stylization. I like fantasy; I like science fiction; I like creating worlds. And rock presented the possibility of creating a whole new fantastic world.

The group presented the greatest problem. At first I wanted to use Sha-Na-Na. I didn't want to try to create a performance group like the Monkeys because I didn't think I could. I wanted to get a group that worked, that had the documentary reality of a real group. But Sha-Na-Na were so large, and they were having problems among themselves so they were very difficult to work with.

JC: You mean personal problems? Intra-group problems?

BDP: Yes. So Paul Williams had always wanted to create a group himself, and he convinced me to do it. And he was right. We were able to create this wacky group out of a lot of actors and singers who sang their own music. A lot of them came out of the Lemmings show or had done improvisational theater before.

BDP: Yes. So Paul Williams had always wanted to create a group himself, and he convinced me to do it. And he was right. We were able to create this wacky group out of a lot of actors and singers who sang their own music. A lot of them came out of the Lemmings show or had done improvisational theater before.

JC: Let's get back to what we were talking about at the beginning: you shot all the sets in L.A., but what about the rest of the movie?

BDP: Well, we had to shoot the theater in Dallas because that's the only place we found which was large enough and still in good repair. It was like an old, spooky opera house.

JC: Lighting a theater like that must have been something!

BDP: Oh, yes. We spent whole days lighting. We rented more lighting equipment than any rental house had rented in about a decade. The English tend to light very heavily, anyway, and I was looking for a kind of hard-edged, comic book-type look. I'd always felt horror and expressionism worked better in black and white because you can get those contrasts. So I tried to also do that with the color. But of course it took a lot of time.

The last concert especially, the wedding scene. We got two cinema verite men from New York, Bob Elstrom and Bob Signorelli, because I wanted the end to look like Altamont. And I had an environmental theater person rehearse a group of rock crazies for a month so they could excite the rest of the audience. In rehearsals this environmental theater guy was so involved in the kind of David Bowie-rock, freak-glitter madness that he totally antagonized everyone in the company. They all loathed him. He was this kind of horrible freak. But that's exactly the kind of character he was in the film: this crazy dancing, throwing the girls around, jumping up on stage, and all that kind of madness looked very excessive in rehearsal. But in the context of the final number it looked just about right; it was totally convincing.

The last concert especially, the wedding scene. We got two cinema verite men from New York, Bob Elstrom and Bob Signorelli, because I wanted the end to look like Altamont. And I had an environmental theater person rehearse a group of rock crazies for a month so they could excite the rest of the audience. In rehearsals this environmental theater guy was so involved in the kind of David Bowie-rock, freak-glitter madness that he totally antagonized everyone in the company. They all loathed him. He was this kind of horrible freak. But that's exactly the kind of character he was in the film: this crazy dancing, throwing the girls around, jumping up on stage, and all that kind of madness looked very excessive in rehearsal. But in the context of the final number it looked just about right; it was totally convincing.

When the Phantom is stabbed and just crawling along he's clapping and stomping and yelling, "C'mon baby, let's see some more of that" -- just totally convincing.

When the Phantom is stabbed and just crawling along he's clapping and stomping and yelling, "C'mon baby, let's see some more of that" -- just totally convincing.

I got that idea basically from DIONYSUS IN '69: in that closed environment, the audience got so involved in the piece that there was a sense of chaos in the room, a sense that anything was possible. And that's exactly the sense I was trying to evoke in the concert scene, where you're not sure exactly what's real and what isn't real. You've seen people shot and stabbed on the stage while performing, so that's an old thing. It's an absurd premise, but you're convinced it's actually happening.

I think this level or reality has come out of television. We're so used to seeing real things happen and seeing films of them that it affects our whole sense of dramatic reality. Someone can't PRETEND to be a politician, like in THE CANDIDATE. You've SEEN Ted Kennedy, so you don't believe Robert Redford's impersonation. You've seen those news conferences; you've seen those people moving around. You no longer buy that whole level of reality anymore. You have to find a whole new acting level.

JC: How many times did you shoot the wedding scene?

BDP: The whole beginning of the number with the girls dancing was all done in parts. But the part when the Phantom swings in, races across and stabs Swan, and then the audience gets revved up and stabs Swan, that we did twice. And we did the Phantom crawling twice -- that's all.

BDP: The whole beginning of the number with the girls dancing was all done in parts. But the part when the Phantom swings in, races across and stabs Swan, and then the audience gets revved up and stabs Swan, that we did twice. And we did the Phantom crawling twice -- that's all.

JC: Twice with how many cameras?

BDP: Five cameras. But these are the kinds of things you can only create once or twice. Once you get them rehearsed, you can let everything work in a kind of improvisational reality because the actors have done it so many times they can go with it whichever way it goes -- the reality lies in what happens to them.

A little like Andy Warhol's first films where they would just turn a camera on for ten minutes. You know whatever happened within that time frame was real because it was a real time frame. It may have been boring or stupid, but suddenly we had a whole new sense of what real was.

And I think when you try to phoney that or synthesize it on the screen, you run into BIG trouble because you do not believe it. Like those convention scenes you see in political movies with everybody jumping up and down -- you can see the extras and the people with signs that have been carefully painted, and you just don't buy it. So that sort of undercuts the whole sense of what you're trying to do.

JC: What are you up to next?

BDP: I'm working on a suspense movie called DEJA VU and writing a screenplay of a book by Alfred Bester called "The Demolished Man," which is about a murder in a telepathic society. I'm changing it and making it an Oedipal murder, a primal murder, the killing of his father. If you're going to do a murder, you might as well do the big murder.

JC: What about his mother?

BDP: Oh, of course he is going to be sleeping with his mother. In the book he's killed his father and he's not sleeping with his mother, but I thought I might as well do the whole thing.

BDP: Oh, of course he is going to be sleeping with his mother. In the book he's killed his father and he's not sleeping with his mother, but I thought I might as well do the whole thing.

JC: Are these being done specifically for anyone?

BDP: "The Demolished Man" is being written for Fox, and DEJA VU is being produced independently.

JC: And if Fox should resist your innovations on "Demolished Man" just

the way Ray Stark and Marty Ransohoff resisted PHANTOM, will you just keep at it until it's done?

BDP: Yes. I do have a reputation for doing projects in the order I want to do them. I believe a director must evolve, and he's the best judge of his own development from film to film. I made SISTERS specifically because I wanted to work in a very tight, structured story form.

JC: In other words, there won't be any Swans making up your mind for you?

BDP: I hope not. It hasn't happened yet, and I've gone this far. And I hope to continue going -- without getting my head caught in a record press!

Interview conducted by John Coates and originally published in Filmmakers Newsletter. Copyright ©1975 by Suni Mallow & H. Whitney Bailey.

I would like to thank Bill Fentum for giving me permission to use the above interview and some of the pictures. Bill has a series of great web pages dedicated to 'Phantom of the Paradise' director Brian DePalma here

- What's It All About? - My Review Of The "Phantom Of The Paradise" Album

- Sleeve Notes From "Phantom Of The Paradise"

- Horror's Ultimate Rock Opena? - Retrospective Reflections on "Phantom Of The Paradise" from Shiver Magazine- The 'Lost' Tracks From "Phantom Of The Paradise"

- Paul Plays Piano In "Phantom Of The Paradise"

- Where To Get The Sheet Music For "Phantom Of The Paradise"

- See Pictures Of Paul Williams As Swan In The "Swan Picture Gallery"

- List Of Other Web Pages About 'Phantom Of The

Paradise'

Hear some rather fun (and rather short) extracts from

'Phantom Of The Paradise' in "The Daily .Wav"

(Thanks to Sarah for telling me about this page)

Email me, David Chamberlayne, at: